An Interview by Brazilian Radical Feminist Aline Rossi with Carol Hanisch and Kathy Scarbrough

Brazilian radical feminist Aline Rossi recently interviewed Meeting Ground editors and long-time activists Carol Hanisch and Kathy Scarbrough for her Portuguese-language blog Feminismo Com Classe . Aline is also a writer/translator in the digital magazine QG Feminista. She currently lives in Portugal, where she helped to found the Lisbon Feminist Assembly, and Generation Abolition Portugal (GAPt), a grassroot collective campaigning for the abolition of the systems of prostitution, womb renting and the sex industry. She participates in the organization of the International Women’s Strike and is an activist in the Antifascist movement.

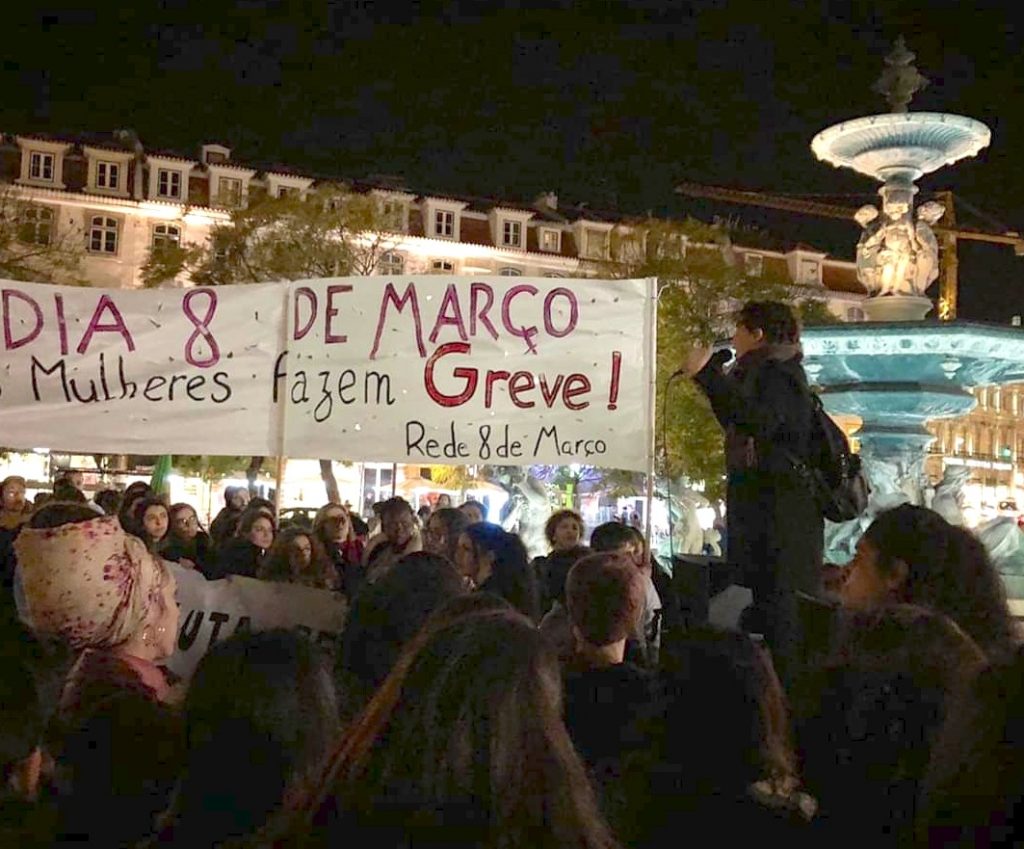

Aline Rossi (with the microphone) addressing an International Women’s Strike Rally in Lisbon, Portugal, one of about 10 cities in Portugal where the strike took place. The banner reads, “On March 8 – Women Strike!” The 3rd line, “M8 Network” is the name used nationally to organize the strike, which included city-level chapters, made of different parties, unionized women, grassroot collectives and individual women.

* * *

AR:

In the 60s-70s, many radical feminists were coming from other movements, as the Civil Rights or the New Left. Women often would be part of multiples organizations and social movements simultaneously. How important was this “multi-activism” to the development of the radical feminist theory and consciousness? How important was it in terms of “radical” as opposed to liberal feminism, or as opposed to “single-issue activism”?

CH:

Involvement in multiple struggles was and still is important, in so far as it is possible – not just to feminism but to the other movements. It did contribute to better theory by radicals then, and that is still true.

We were enormously influenced by the Civil Rights, Black Power, and Labor Movements. Even those who didn’t participate in them directly felt their impact. It was a time of great learning for most of us, a harsh facing up to what really was going on behind many deceptions that had passed for truth in the U.S. We learned about race, class, imperialism (especially in the Vietnam War), and poverty and the repression and suppression used against those who fought for rights and liberation. We are going through another grand exposure now on just how “unexceptional” the U.S. really is, including on how much the founding and prosperity of “America” by Europeans was based on African chattel slavery and exploitation of immigrant people of color and indentured white labor, the colonizing and slaughter of native Americans, and the repercussions.

After several decades when anti-communism forced these truths underground, many of us came into the 1960s having to re-evaluate and re-learn our history – feminist and radical – as well as learn how deep the awful conditions of the present were. And we are still learning.

Women had always been active in radical movements, though often forced to work behind the scenes. The Civil Rights/Black Power and other movements taught us how to think about our own oppression as women and the importance of organizing ourselves into a force to be reckoned with, instead of trying to rise above our lot individually. We saw others winning some liberation and therefore believed it was possible for women as well. We also had the influence of socialist revolutions in other countries. The Chinese revolution had a big impact on some of our theory. We see the influence of the “Tell it like it is” from the Civil Rights Movement and “Speak pains to recall pains” from the Chinese revolution being combined with “Bitch, Sisters, Bitch” on a poster we hung in New York Radical Women consciousness raising meetings in 1968. It was a method that had been successfully employed before us.

AR:

I feel that despite that younger generations of women are growing in a moment when feminism is “fun” and even “mainstream”, ironically, these young women are harder/less likely to organize in real groups, real collectives, and organizations. It seems like “solo activism” is the newest trend, a sort of “entrepreneurial feminism” where a woman alone can do her work and that’s enough. What do you think about it? Are we failing to recruit women?

CH:

We are all failing to organize ourselves in a powerful enough way and we should look at why that is. Some groups are active but small, and we’ve failed to develop a structure and theory capable of uniting an organization with enough power to make big changes. And it’s not just in Women’s Liberation. Movement groups easily fall apart, or at least don’t have enough punch to attract and hold onto growing members. Frankly, many of us old-timers look back and see how much remains unresolved, and that we’ve lost much of what we won while the theory that made it possible has been buried. Meanwhile daily life has become more demanding and frustrating. The huge disparity between the one percent and the rest of us and the bleak outlook for the planet exhausts hope and patience. We stop thinking big and look for a little relief here and there.

Our Movements, like the rest of society, are pelted with the ideology of individual success as opposed to winning liberation for all. The worshiping of celebrities and the personally “successful” is part of this. Some women spend their time only cultivating their careers or personal “empowerment” and sometimes even attack the feminist movement that made their success possible. It is overriding and damaging to Movements when competition between individuals and groups leads to lack of unity. The convenience of social media and the internet leads many to believe that clicking and commenting there is all that needs to be done. Today’s “American Dream” is to get the most clicks!

Then too, our attention keeps getting pulled away from the daily life oppressions of the common woman/person and jumping from one urgent situation after another, often with no common understanding of the connections or how to build these single interest groups. We seem not to be able to get beyond the small “affinity group” approach. There is no one organizing the organizers. Meanwhile, liberal single-issue groups that are well funded, usually by corporate or rich individual foundations, are able to plant and grow their liberal political line and swamp us. In the beginning we did a lot with very little money. There’s no way we are ever going “out money” them, so we are going to have to find other ways to get the job done.

KS:

I’ve heard Carol talk about the need to organize the organizers before. Just contemplating that concept is interesting. It might be OK to have dozens of small groups if the organizers worked together. Agreement in a small group is easier than in larger groups where much time is spent trying to find it. But small groups aren’t powerful enough alone so we need a way to federate small affinity groups for increased power.

In terms of your other question, it seems to me that many women are spending so much time on social media, talking to each other and sharing articles as well as carrying on polemics with opponents that there is no time or interest in on the ground, face to face organizing. It’s good to share and figure out what is going on but then we’ve got to DO something with that knowledge! Create a program for collective action. I am in a group that is trying to recruit women for collective action but there is great competition with our own member’s social media efforts.

Social media can be powerful in starting a national discussion but we need to learn more how to use it powerfully and not get mired in it.

CH:

“Fun feminism” is part of current culture’s attempt to entertain ourselves to death – sometimes literally. It’s new only in the degree. It is flabbergasting that many women find “fun” the items of “female torture” that we threw in the Freedom Trash Can at the Miss America Protest in 1968. But some tried to make the Miss America Pageant Protest focus on “having fun” then, too. Very little of what we face today is new.

AR:

Radical feminists are still the main players in the front fighting to abolish prostitution and the sex industry today. And these are mainly legal reforms. Now, we know the importance of reforms for women – voting, studying, abortion rights, etc. – but as these struggles can be very time-consuming, one can easily become a single-issue activist. Doesn’t that blur the lines on radical action and reformism? Where is the line here, and how can we balance both so we won’t lose our north?

CH:

Single issue organizing is best when imbedded in a group with a common view and position on the whole and with an articulated program to guide the work. How to do that successfully is not yet clear to me, especially in our current situation where radicals are mostly not very effective in the big picture. Some of this may be because of our own shortcomings, but part of it has to do with being scattered both physically and theoretically. There are no uniting radical feminist publications that combine theory and action. Unity cannot just be demanded or called for, it has to be understood and forged in practice. Even mention theory and many feminists either object to it as authoritarian or role their eyes, but people cannot unite without shared theory. On the other hand, we have academics who want to “theorize” feminism with no connection to practice, to action, to accurate history, or especially to putting theories to the test. The struggle over theory is irrelevant unless it is a struggle for the truth, not about showing how smart you are.

Some people find it much more comfortable to work on single issues as it seems easier. It means they don’t have to put thought into defending or advancing the whole. A single issue can seem more “do-able” without the “baggage” of the whole, but the power of the whole can give essential support to the single issue that propels it forward and keep it moving in the rare situations where reforms are won. When reforms are not part of a clear program of what we really want and need, their partial victory can cause the radical goal to disappear, or at the very least momentum is lost and we have to start from scratch.

The big question for single issue organizing is, “How does it get integrated into the whole to make the whole more powerful?” How do we handle the winning or losing of the limited fight – or more likely, how do we deal with the partial victories or reforms that get offered to shut us up while not granting what we are really fighting for?

I keep thinking there must be a way to use reforms to demand MORE rather than resulting in most people going home with a sigh of relief when some little piece is won, which is essentially what happened with the abortion repeal fight that sought to give women power over our own bodies. The Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision was based on privacy issues, and did not recognize abortion as a woman’s right. It also contained a number of restrictions, which left the door open to the hundreds more that have been added since. Abortion has gradually become unavailable in 90 percent of the counties in the U.S., even though it is still thought of as “legal” unless the Supreme Court overturns Roe vs. Wade.

KS:

The partial abortion victory shows how race and economic class impact the work of women’s liberation. How would you describe the relationship Cindy Cisler (and others diving deeply into the abortion issue in the late 60s early 70s) had with the women’s liberation movement as a whole?

CH:

Cindy was deeply embedded in New York Radical Women, one of the seedbed groups in the U.S. She came to meetings, participated in consciousness-raising and in actions other than abortion. She was involved in the Miss America Protest and helped with the publication of NOTES FROM THE FIRST YEAR. She raised our consciousness about the importance of repeal vs. reform, which many of us acted on, which in turn strengthened her work for abortion repeal.

AR:

Since we are here… What does it mean to be a radical feminist in terms of political practice, anyway?

CH:

To me it means facing, analyzing and attacking female oppression at its roots, no matter what, and keeping what we really want upfront and center. It means being willing to take the risks of going where the faint-hearted fear to tread – to fight for the truth, to lead, to tackle new ground, to put the necessary thought into the unresolved. To be good at freedom fighting, one has to be a freedom fighter. I cringe when I hear academics talking about how they are “theorizing” women’s liberation, usually to make it less threatening to the powers that be.

KS:

It understands that women as a class will never be free under capitalism or under conditions of white supremacy and acts accordingly. It’s not about “getting yours” under the current system, it’s about changing the entire system.

CH:

Yes, that’s pretty basic. At the same time, we need to remember that the Women’s Liberation Movement’s job is to focus on ending male supremacy, while we simultaneously tackle all that stands between us and liberation. Women are so easily convinced to put the needs of others ahead of our own. We’ve learned from experience if we don’t fight for ourselves, no one is going to.

AR:

Even though many radical feminists came from the Marxist left – and, IMO, it’s hard to deny the influence of Marx in radical feminist theorization – many radfem writers say that the relationship with the so-called “socialist feminists” was not that good. It was not only controversial but often antagonist in many topics. Why was that? What can you tell us about the WLM’s relation with the left in those early days?

CH:

It’s too complicated to explain well briefly. The 1960s and early 1970s were a time of great turmoil and much learning. Our understanding of terms like socialism, communism, feminism, radical, liberal, and so forth was in process. Still is, of course. In the 1960s we were just emerging from a very anti-communist period when any association with socialism or Marx could get you in a lot of trouble, if not killed. Most of us were very disconnected from that history, which held back our thinking. The term “socialist feminist” represented a broad spectrum and still does. Some wanted little to do with Marxism and others wanted little to do with feminism – and everything in between. Some were very attached to the New or Old Left organizations they participated in and were reluctant to offend the men in them by pointing out that men oppressed women. Some saw sex as a class similar to economic class, while others attributed women’s oppression only to capitalism, while others maintained it is rooted in both. Again, a lot of this was skewed by the fact that being called a socialist or communist can bring punishment or dismissal as “old hat”. As a result, an understanding of these terms is still not very unified.

A primary division in the very early years was between what was called the “feminists” and the “politicos.” Many “politicos” put the blame on “the system”. This could mean capitalism but it often came with a large dose of psychological “rooting”. The “politicos” originally agitated mainly for better treatment and leadership roles within the New Left, primarily Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), while the “feminists” (actually radical feminists) took on the broader society. We knew that we wouldn’t get better treatment from Left men in isolation, because we all live in the broader society and feel its pressures. For example, radical feminists believed men as well as capitalists benefitted from oppressing women and clamored for both public childcare centers AND demanded men share the housework and childcare. Many groups were composed of both tendencies and they often overlapped. Eventually we came roughly under the umbrella of women’s liberation.

Many of today’s “RadFems” are not very interested in either the issues of socializing housework and childcare and getting men to share it or in the changes that need to be made in the broader society to make those changes possible. For example, we will never have free good public childcare while capitalists appropriate the money from our labor in both the public and private (family) work arenas and waste our taxes by the trillions on the U.S. military machine. I have had disagreements with some RadFems who claim men are free and not exploited by anything, not even capitalism, and don’t see a reason to unite with them. Many early radical feminists maintained that men were both oppressors AND needed allies in the struggle for socialism, but we would need to build a very strong women’s liberation movement to bring that alliance about.

AR:

Radical feminists are openly left-wing, some are communists, others are anarchists, Maoists, etc. But there is also a wide range of radfems who refuse the influence of Marx in our theory – because he is male; or who says that we can’t count on Marxists and leftists because the URSS has failed with women, and today’s left organizations are still male-dominated and support anti-women agenda. What do you think about it? What do you think it should be, now, the relationship between the feminist movement and the broader left (especially left parties)?

CH:

They are right that most of the Left is still male dominated and opposed to real feminism, but to ignore male supremacy in the Left is not going to work. Radical feminists must continue to fight the male supremacy in the Left from both within and without. Every left group should have a FEMINIST caucus, rather than a WOMEN’S caucus. Many of today’s RadFems seem to be more the political descendants of the radical lesbians and cultural feminists, who were often separatists. They appropriated the term “radical feminists” to mean “extreme” more than “at the root.” Many still consider withdrawing from relationships with men the most “radical” thing one can do and the issues that interest them most do not include those of relationships with men and childcare/housework that most women have to deal with in their daily lives. That has not boded well for organizing a mass movement.

The dismissal of the USSR as a complete failure, including gains for women, is the result of deliberately distorted history. Women and working people WERE making important gains under socialism/communism before it was suppressed by imperialist backlash, often led by the U.S., as well as internal mistakes that get made when one is attempting something so huge and new. Most history, even that written by those who call themselves socialists, does not talk much about that. Women in many socialist countries got the vote before we did in the U.S. They also made forays into trying to solve the problems of childcare and housework. Meanwhile, the U.S. has still not even passed the Equal Rights Amendment assuring women basic legal rights!

As uncomfortable as it may be, women have no choice but to continue to fight against male supremacy and for support of women’s liberation within Left formations, including parties. To do otherwise is to be left behind. Neither half of the population can shut out the other half and expect a good outcome. We are up against such powerful forces that we need everybody on board. We have to be careful though when we hear men say, “Let the women lead.” Somehow this strikes me as another way of men not doing their share of the revolutionary work, since it is so hard and not immediately rewarding.

KS:

I don’t see how one can identify with radical feminism and not consider Marx. This seems like such a dismal shrinkage of what radical feminism was and I attribute it to the rise of single issue organizing on rape, porn, prostitution and violence against women. These issues are important but we’re never going to get anywhere on prostitution and porn if they are divorced from an understanding of capitalism. We have to fight against the capitalist exploitation of our bodies as well as against the idea of male entitlement to women’s bodies. Both are oppressive. Interestingly, in my experience it is more often the socialist feminists (as well as the majority of the male dominated left) who accept prostitution and porn as “sex work.” Feminists are part of the Left. We need to continue to struggle with Left groups but from our own independent base of power. I’m not a member of any left party but I am aware that feminists are fighting hard within the Green Party here in the U.S.

CH:

The New Left “politicos” were much more into the psychological. Some of the “feminists” were much more influenced by the Old Left and the labor movement. Interestingly, much of the theory that came out of this group was more materialist, like the pro-woman line, which asserted women are “messed over” (oppressed), not “messed up” (need to change ourselves). I was among the materialist group, even though I didn’t feel right calling myself a Marxist because I’d never read much beyond the Manifesto. Also, many who called themselves Marxists were very critical of Women’s Liberation, which caused many of us to resist reading Marx at first. When we finally did go to the source, we discovered they often quoted Marx wrong. Large parts of the New Left were anti-communist. For example, Vietnam: Some were just against all war or opposed the military draft or opposed war as a moral issue. Some sided with the Vietnamese National Liberation Front in its fight to liberate Vietnam from U.S. imperialism. It was very much a mish-mash and therefore not as strong as it could have been.

KS:

That’s interesting from the perspective of building a larger movement from smaller affinity groups. Were the antiwar coalitions that broad or was it the situation that a fairly cohesive group would call a demonstration and the others just came with their own demands?

CH:

There is a difference between mobilizing and organizing ongoing organizations and movements. The huge mobilizations against the war were often coalitions with each group listed in the publicity and each retaining their own slogans and signs at the marches. Sort of like the recent Women’s Marches. There was always an attempt to downplay or shut up the radicals, though.

AR:

One of the challenges we have now is the left hegemonic support to the trans narrative in detriment of the women’s liberation agenda. Now, I can see this has become more than a theoretical problem or more than an issue of capitalism benefiting from offering highly medical/surgical/cosmetic solutions to social issues. As the transgender ideology affects more and more working-class people (including numerous women, mostly young lesbians), how do you think we can address this neoliberal take-over of the feminist movement and the left? How can women respond to that?

CH:

We certainly have to raise people’s consciousness about what this means not just for women, but also for the Left and society as a whole. There is something very dangerous for all of us to allow what is not based in reality to pass as truth, and even pressuring others to get on the fantasy bandwagon, like being forced, by law even, to use pronouns that defy reality. There is a strong connection here with “postmodernism”, another academic contribution to subverting scientific materialism. Much of the Left is abandoning its own claim to scientific materialism and refusing to support half the population and just when objective conditions are on the rise for what could be a great leap forward. I doubt this divisive ploy is accidental.

KS:

This is particularly difficult because, of course, we believe in civil rights for everyone. And its not just the Left support of the trans narrative – many mainstream institutions have bought into it, for example libraries, motor vehicle departments, state governments. In New York City you can be fined $250,000 for “misgendering” someone. The trouble is that it pits “trans rights” against women’s rights. Women need the right to public female-only spaces precisely because of the violence and threat of violence we face daily. Women fought for and won some programs that are aimed at leveling the playing field and we aren’t going to give those up. Transgender people need civil rights protections and Feminists in Struggle – a newly formed feminist group – believes this is best done by creating a new category for civil rights protection: sex stereotyping. One should not be discriminated against for manifesting behaviors, dress, appearance, grooming, etc., typically associated with the opposite sex. Protection against sex stereotyping would help a lot of women too.

CH:

Radical feminists want to do away with gender, not support its expansion. There have always been men who thought that women have it better than men, and transwomen are acting on that in their own way. Transmen, one the other hand, are abandoning the feminist struggle with a personal solution of sorts, which they have a “right” to do, but that’s not good for women’s liberation and is therefore open to critique by feminists.

KS:

It seems true that a number of people would choose to do this to themselves in an effort to escape the chains of male supremacy rather than work to change the world so everyone can feel comfortable in their own bodies. Raising the consciousness of parents to the politics involved (so they respond appropriately when their child expresses unhappiness with being a girl or a boy) and young lesbians is particularly important. It seems that the lesbian community in the U.S. is quite active in this area already. It is a core feminist message that we are FORCED to conform to sex stereotypes or be punished. None of us – women or men – fit these stereotypes. Gender pressure must be abolished, not conformed to, or excused. But abolishing these stereotypes once and for all takes a movement; we cannot do it individually.

AR:

If back then, in the times of the WLM, when the movement was even on the lists of CIA, women already had to deal with the leftist outcries about feminism being “identity politics”, now, after a massive neoliberal take-over, the outcry is louder than ever. How do you see this issue of “identity politics”? Is there really an “identity feminism”? If yes, how do we counter that?

CH:

Female oppression is not an “identity”. Females are half the population, the sex currently exploited by both capitalism and male supremacy. At the root of women’s oppression is our capacity to bear children, not how we think of ourselves. The reduction of sex (and race) to “identity politics” by the Left (and it’s not just white males) is an attempt to shut up and stop our movements for liberation. We have to fight for reality, even if it means not being “nice” women. A revolution, as Mao once said, is not a tea party.

KS:

Just knowing that the accusation of “identity politics” is a way of trying to dismiss your concerns is very helpful in countering it.

AR:

Many feminists criticized the lack of structure in the feminist movement political organization. Among other things, they usually point how it worked to corrode the movement from within. In terms of organization, what was wrong? What was right? What advices would you like to give to younger feminists in order to a better organizing?

CH:

This is a huge problem. One size does not fit all. To some degree the loose structure in the early days of consciousness-raising was a strength because it allowed large numbers of women to participate and the movement to grow rapidly. You didn’t need a college degree or other credentials. People always need their own struggle experience to really understand and learn how to contribute to the fight. However, the lack of structure turned into a weakness when it came time to agree on theory, take actions and consolidate our power once the movement had spread. Not having a workable structure also permitted any woman to present herself as a spokesperson for the movement without the experience, understanding, and accountability to do so. Self-promoters, often which the help of the mass media, saw an opportunity and ran wild, ruining the work of building actual unity around mass demands.

It’s always best if a group or movement can reach a consensus, but when it can’t, voting can be necessary to move forward. We must have unity to build enough power to make the kind of difference that can liberate us. Simply ordering people about doesn’t usually work very well. You have to make a good case for why people should cooperate with you or your group. There is no magic bullet to solve the structure problem. We have to look around us and back in history to see what works and what doesn’t at certain stages of development and be willing to update when what we are doing doesn’t meet our needs.

KS:

I would add that our current level of individualism presents problems here. Often when consensus fails and the group decides to vote, those who lose the vote quit the group. We’re never going to become powerful if good feminists don’t stay in groups and fight for what we think is right. AND also accept that sometimes you haven’t been able to convince others.

CH:

We have all dropped out of groups – or been forced out of them. Sometimes the group isn’t what we expected. I wouldn’t say a woman should ALWAYS stay in a group that doesn’t suit her as her presence would not be constructive for either the group or the individual. But in that case, it’s necessary to find another group or form a new one that does work for you and look for ways to ally with other groups when possible. Small groups are not ideal and should never be a goal in themselves as they aren’t often much more powerful than an individual, but sometimes they are the best we can do.

The original of this interview is posted in Portuguese here.

# # #

“Our Movements, like the rest of society, are pelted with the ideology of individual success as opposed to winning liberation for all. The worshiping of celebrities and the personally “successful” is part of this.”

Yes! And there’s something I find curious and hilarious about that: this worshipping of celebrities coexist with the contempt of theory and political practice. Suddenly, we don’t need a social movement for fight for our rights, we just need an individual “empowered woman” to represent all of us. Even if she is an imperialist or a soldier who serves a genocidal state. This false image of the feminists purposes keeping us away from the working-class people and a truly women’s liberation.

“In terms of your other question, it seems to me that many women are spending so much time on social media, talking to each other and sharing articles as well as carrying on polemics with opponents that there is no time or interest in on the ground, face to face organizing.”

I agree! And many women(but not only women, people in general on social media) on internet reduce complexes social movements with a very long time and work to the mistakes of a “virtual ‘militant’ star”. There are many others that transform theories into a lifestyle desconected of the real world.

” “Fun feminism” is part of current culture’s attempt to entertain ourselves to death – sometimes literally. It’s new only in the degree. It is flabbergasting that many women find “fun” the items of “female torture” that we threw in the Freedom Trash Can at the Miss America Protest in 1968. But some tried to make the Miss America Pageant Protest focus on “having fun” then, too. Very little of what we face today is new.”

This part made me remember an interview where Gail Dines talked about how many women see feminism as “make sex with how many men we can” and not a political movement and how it keeps them away from the feminism. Liberal women like to believe that feminism is reaching its goals because actually the name “feminism” is on the media as never before. Well, it’s a fact that “feminism” is popular today, but it isn’t that good. Feminism are on the media today because it was de-radicalized and adapted to the capitalist market. That is, it is not feminism at all. I cannot forget to mention how sad it is to see that even the issues of women’s oppression are not portrayed in a feminist way. The most serious issue is the men’s violence against women. But in this age of empowerment, it is very common for the media to imply that women today are only in situations of abuse because they have not “empowered themselves” enough. It is the old blame of the victim, now disguised in a less aggressive speech. To think how absurd the situation is, actually the porn industry has adopted the rhetoric of “combating violence against women”. This refusal by liberal women to connect sexual oppression to pornography, prostitution and bdsm is frightening.

“When reforms are not part of a clear program of what we really want and need, their partial victory can cause the radical goal to disappear, or at the very least momentum is lost and we have to start from scratch.

The big question for single issue organizing is, “How does it get integrated into the whole to make the whole more powerful?” How do we handle the winning or losing of the limited fight – or more likely, how do we deal with the partial victories or reforms that get offered to shut us up while not granting what we are really fighting for?”

The situation is really complex! Many segments of the left are supporting a lot of forms of the male supremacy. One of the most notable are women as subjective feelings and the sex industry. When we refuse to secundarize our own oppression, we suffer retaliation and exclusion from groups and unions. The far-right, of course, takes advantage of these situations because it wants to destroy the left as a whole, but it offers “support” for certain positions that many leftists despise, which leaves many feminists swayed. I see that this situation is affecting the radical feminist organization a lot. First, because many are adopting a reactionary separatism that was never part of the movement. Second, because many of them think that radical feminism is limited to male violence and transsexuality. When these issues are not at stake, they tend to think that there is no reason to maintain activism and that is bad. I talked a lot with a longtime friend about it (“how we can combat these reactionary and identity tendencies that hinder the movement”) and Aline (the interviewer) and I also touched on this subject many times and the frustration is great. Still, I think works, articles, texts that aim to demystify radical feminism and lead it to another activisms are very important.

“Many of today’s RadFems seem to be more the political descendants of the radical lesbians and cultural feminists, who were often separatists. They appropriated the term “radical feminists” to mean “extreme” more than “at the root.” Many still consider withdrawing from relationships with men the most “radical” thing one can do and the issues that interest them most do not include those of relationships with men and childcare/housework that most women have to deal with in their daily lives.”

It honestly worries me deeply. Because most of them aren’t even radical feminists, but they usually make a counter-propangada against radical feminism from the inside and promote many distortions in name of the movement. A big example of this is the “Female Biology Superiority”, where we can see good arguments against this idea on Radical Feminist tradicion(Barbara Leon, Andrea Dworkin, Kate Sarachild, Carol Hanisch, etc), but it is still supported by many “radfems” in total contradiction with radical feminism.

“The dismissal of the USSR as a complete failure, including gains for women, is the result of deliberately distorted history. Women and working people WERE making important gains under socialism/communism before it was suppressed by imperialist backlash, often led by the U.S., as well as internal mistakes that get made when one is attempting something so huge and new.”

This de-radicalization of social movements today was an effective way of containing socialism. I think it is positive to criticize and analyze what went wrong (and why it went wrong), but when they reduce complex events to “socialism / communism failed because it was led by men”, we see how much we need to work on class issues.

“As uncomfortable as it may be, women have no choice but to continue to fight against male supremacy and for support of women’s liberation within Left formations, including parties.”

I feel uncomfortable when some people on Feminist/Black movement reduce the left policies as a whole to the racism and misogyny of the some leftists. Women (of all colors) and people of color (of both sexes) was always present in the left and they developed the left, too. The left isn’t a private property of the white males leftists, which is not to say that there is no racism and sexism within the left. Unfortunately, it exists, because these forms of oppression can only be overcome through an organized and lasting struggle, besides that, racism and sexism are not individual errors and are part of a much larger system. What I mean is that to insist on the idea that racism and sexism is what defines a leftist policy, instead of the struggle for a classless world, we will be accepting the liberal distortion of the leftist policy, in addition to erasing the contributions from women and people of color who were socialists, communists and anarchists and used these theories as a guide for action.

“I don’t see how one can identify with radical feminism and not consider Marx. This seems like such a dismal shrinkage of what radical feminism was and I attribute it to the rise of single issue organizing on rape, porn, prostitution and violence against women. These issues are important but we’re never going to get anywhere on prostitution and porn if they are divorced from an understanding of capitalism. We have to fight against the capitalist exploitation of our bodies as well as against the idea of male entitlement to women’s bodies. Both are oppressive”

Another thing that I realized throughout my observations and research, Kathy, is that these women tend to use these issues as a form of alienation in a male supremacist world, in the sense that men are evil by nature and prostitution, pornography and physical violence are the proofs of that. And that in itself already undermines this more specific struggle, as appealing for biological reductionism is a serious and also anti-feminist error.

“It seems true that a number of people would choose to do this to themselves in an effort to escape the chains of male supremacy rather than work to change the world so everyone can feel comfortable in their own bodies.”

I think the issue of transsexuality is very complex. I mean, there are really misogynist men (and there are not a few) with a fetish for being a woman and other cases where psychological, emotional and physical suffering is real. But it bothers me a lot how these issues are approached sometimes, as if we were the villains of the history and some women who identify themselves as radical feminists seem to support this view that we are the ones who “exclude” trans people. We fight male supremacy, while much of the trans movement supports this (although they reject the violence and stigmatization inherent in male supremacy to people perceived as “wrong”). But as I usually talk to my friends whenever this issue comes up: the inherent misogyny of transactivism does not represent trans people as a whole. Many transsexual people, like Miranda Yardley, understand that the oppression of trans people originates from the intimate and complex connection of male and white supremacy with capitalism, and not from a society where the majority is “cisgender” and a minority is trans. I strongly believe that we can (and should) combat the systems that oppress us together with transsexual people that have the same goals and maintain separate bases of power for specific organizations.

“Female oppression is not an “identity”. Females are half the population, the sex currently exploited by both capitalism and male supremacy. At the root of women’s oppression is our capacity to bear children, not how we think of ourselves. The reduction of sex (and race) to “identity politics” by the Left (and it’s not just white males) is an attempt to shut up and stop our movements for liberation.”

This excerpt reminded me of a very good text that I was reading about the left and identity, about how it move away the working-class and the author gave very interesting examples, showing that workers want to know about family support and jobs and that the way certain debates about racism, abortion and sexuality are produced move away these people. I agreed because it is true, but disappointment followed when the author reduced the problems of the black and feminist movement to “identity issues”. It is said that the major concern of black poor people/ poor women is not racism or sexism, but the economy and this is also true when people are not organized into specific movements, but the author (who was a white man) totally ignored that the existence of white and male supremacy further worsens the living conditions of poor people.

I loved this interview. I hope to see more Brazilian radical feminists on MG.