Commemorating 50 Years of “Sisterhood Is Powerful”

by Carol Hanisch

Fifty years ago, the Vietnam War was raging and so were protests against it, the intensity and scope of which would increase multifold in 1968.

On the opening day of Congress on January 15, 1968, a coalition of women’s peace groups, headed by Women’s Strike for Peace, gathered in Washington D.C. to add their voices as women in protest against the War. Some 5,000 women showed up at a time when many women were still expected to be home caring for husband and children, not trying to influence national affairs. It was the largest march of women since the suffrage marches of more than 50 years before.

The march was called “The Jeannette Rankin Brigade” after the first woman elected to Congress in 1916. She was also one of the few suffragists elected to Congress and the only member of Congress to vote against U.S. participation in both World Wars. She was elected with the help of women in her home state of Montana, which had granted women full suffrage rights in 1914. She ran pledging to work for a constitutional woman suffrage amendment and emphasizing social welfare issues. At 87, she walked at the forefront of the Brigade marchers.

• • •

However, the 1968 March would prove to have even greater significance than women stepping out for peace. Radical women’s groups and individuals also showed up with what was then an unusual agenda. As Shulamith Firestone, a founder of New York Radical Women, wrote in NOTES FROM THE FIRST YEAR:

[F]rom the beginning we felt that this kind of action, though well-meant, was ultimately futile. It is naive to believe that women who are not politically seen, heard, or represented in this country could change the course of a war by simply appealing to the better nature of the congressmen. Further, we disagreed with a woman’s demonstration as a tactic for ending the war, for the Brigade’s reason for organizing AS WOMEN. That is, the Brigade was playing upon the traditional female role in the classic manner [as] wives, mothers and mourners; that is, tearful and passive reactors to the actions of men rather than organizing as women to change that definition of femininity to something other than a synonym for weakness, political impotence and tears.

These mostly young radicals had come to Washington less to protest the war – though they too adamently opposed it – than to persuade the “peace women” that women needed a movement of their own to achieve power for women before they could make much of a difference on the public sphere.

Following the march, participants convened in a large auditorium. Much negotiation and agitation had taken place over what would be permissible by the March organizers and for a speaking spot on the post-march program for the upstart New York Radical Women, the initiators of the radical feminist component. The speaker, Kathie (Amatniek) Sarachild, gave “A Funeral Oration for the Burial of Traditional Womanhood” (printed in NYRW’s NOTES FROM THE FIRST YEAR) which stated, in part:

Now some sisters here are probably wondering why we should bother with such an unimportant matter at a time like this. Why should we be burying Traditional Womanhood while hundreds of thousands of human beings are being brutally slaughtered in our names—when it would seem that our number one task is to devote our energies directly to ending this slaughter or else solve what seem to be more desperate problems at home?

Sisters who ask a question like this are failing to see that they really do have a problem as women in America – that their problem is social, not merely personal – and that their problem is so closely related and interlocked with the other problems in our country, the very problem of war itself – that we cannot hope to move toward a better world or even a truly democratic society at home until we begin to solve our own problems. …

Yes, sisters, we have a problem as women all right, a problem which renders us powerless and ineffective over the issues of war and peace, as well as over our own lives. And although our problem is Traditional Manhood as much as Traditional Womanhood, we women must begin the solution.

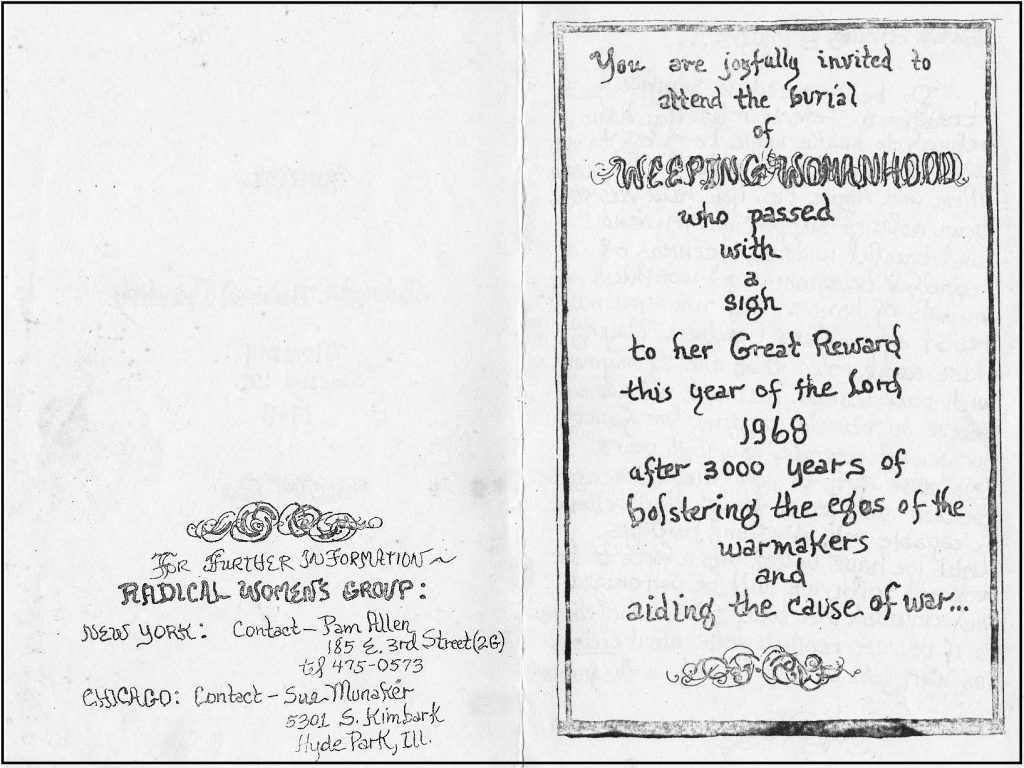

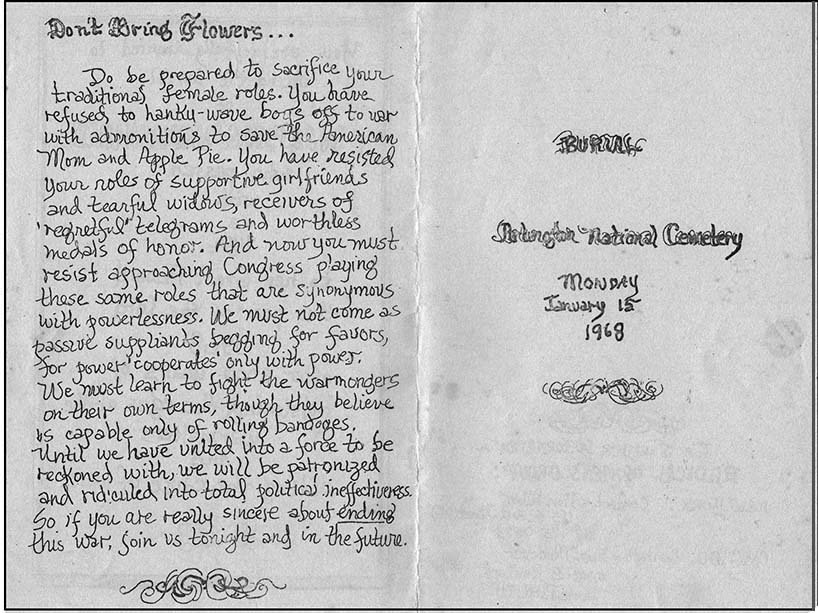

Sarachild’s speech had been preceded by a funeral procession to the front of the auditorium of an oversized female dummy on a bier from which hung such items of femininity as curlers, garters, ribbons and hairspray. The radical women had also distributed a black-bordered “Invitation to the Burial of Traditional Womanhood,” who “passed with a sigh to her Great Reward this year of the Lord, 1968, after 5,000 years of bolstering the egos of Warmakers and aiding the cause of war….”

The artistic invitation created by Shulamith Firestone, read, “Don’t bring flowers,” but:

Do be prepared to sacrifice your traditional female roles. You have refused to hanky-wave boys off to war with admonitions to save the American Mom and Apple Pie. You have resisted your roles of supportive girl friends and tearful widows, receivers of regretful telegrams and worthless medals of honor. And now you must resist approaching Congress playing these same roles that are synonymous with powerlessness. … Until we have united into a force to be reckoned with, we will be patronized and ridiculed into total political ineffectiveness.

The protest included radical women’s groups and individuals from around the country. Addresses for fledgling feminist groups in both New York and Chicago appeared on the invitation. Firestone had been influential in organizing the Chicago group before moving to New York and co-founding the New York group and she involved both in the protest, which also spread by word of mouth.

The Birth of Sisterhood Is Powerful

What was to become the popular concept that “Sisterhood Is Powerful” was first introduced by Kathie Sarachild in a flyer she prepared for the Brigade that laid out women’s progression and a strategy toward “humanhood” for women:

Traditional womanhood is dead.

Traditional women were beautiful…but really powerless.

“Uppity women were even more beautiful…but still powerless.

Sisterhood is powerful!

Humanhood the ultimate.

A group of about 500 split off from the main conference program into a radical caucus. They had been leafletted with an invitation from the New York and Chicago groups in anticipation of such a meeting.

There was much disagreement on what should be done next. Some argued for more militancy by women against the war. Others contended even this would be futile as long as women were considered to be secondary to men, that women needed a movement of, by and for women to unite for power for women first if they were ever to be taken seriously.

The feminist faction soon found they were not alone. Connections were made that led to strands being pulled together toward what would soon be called the Women’s Liberation Movement. Joreen Freeman agreed to edit a newsletter (eventually called Voice of the Women’s Liberation Movement) to keep in touch and share ideas. Several women went home inspired to start groups. Existing groups expanded.

• • •

So January 15, 1968, went down in history as an important date in the feminist explosion that was to follow. The road ahead was to prove even more difficult than most expected and 50 years later finds us with some improvements in women’s situation but far from our goal of women’s total liberation.

The milestone made me think of 19th century feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s closing remarks in a speech on the 30th anniversary of the 1848 Senaca Falls Convention as she reflected on the long struggle her generation had experienced:

The full fruition of these years of seed-sowing shall yet be realized, though it may not be by those who have led in the reform, for many of our number have already fallen asleep. But we have smoothed the rough paths for those who come after us. The lives of multitudes will be gladdened by the sacrifices we have made, and the truths we have uttered can never die.

Memory recalls many duties in life’s varied relations we would have had better done. The past to all of us is filled with regrets. But I think that we should all agree that the time, the thought, the energy we have devoted to the freedom of our countrywomen, that the past, insofar as our lives have represented this great movement, brings only unalloyed satisfaction. The rights already obtained, the full promise of the rising generation of women, more than repay us for the hopes so long deferred, the rights yet denied, the humiliation of spirit we still suffer.

No compromise with oppression! Fight on!

To respond to this post, please send comments to MeetingGroundOnLine@verizon.net