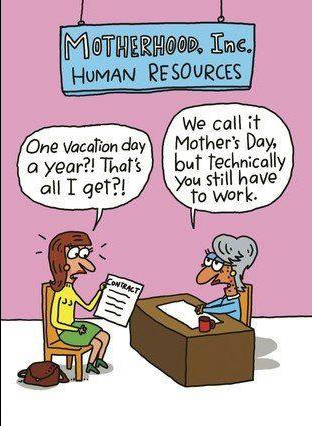

A Consciousness-Raising Discussion about Motherhood and Birth Regret

The public is often harangued with stories of supposed “abortion regret”. A recent on-line discussion resulted with its opposite: birth regret. Women discuss their often mixed feelings about having given birth — or not — and its effect on their lives. We publish lt here as a realistic response to Mother’s Day. —The Editors

<O>

Susan:

I marched in New York for the big women’s march carrying a poster I made that said ABORTION IS EMPOWERMENT—SAVE ROE V. WADE. My reproductive years are way behind me but abortion rights are my ongoing issue.

* * *

Jane:

Susan, you were quoted in some magazine article as saying, “I have always known that I wasn’t meant to be a mother.” That struck me! I thought you were courageous and forthright and honest and revolutionary. And gloriously anti-the world’s expectations of you.

I was affected personally too. Because it is, oh, so difficult to find out that one was not meant to be a mother after you already are a mother. Much is made by the Right-to Lifers of “abortion regret.” No one ever talks about birth regret. So darling Susan, you carried that sign for me, too.

* * *

Kathy:

I like that, “birth regret”! I bet many women have experienced it.

* * *

Ti-Grace:

Jane, you just coined a new important phrase, “birth regret”! I wonder how many women have suffered from this and could never admit this even to themselves. “Oops! Too late.” And sentenced to a lifetime of childcare, one way and another. I’m sure many love their particular children but the “mother” role is a major bitch.

You’ve got guts!! Essential for a feminist. “Stubborn” is good also. Everyone on this list qualifies as “stubborn”.

* * *

Susan:

Yes! “Birth regret” explains the new mothers who are unable to cope with their babies and violently abuse their newborns. I don’t doubt the scientific evidence supporting postpartum depression, but it is not the whole story.

* * *

Carol G:

I think “birth regret” is wide spread and in my experience women do talk about it. Many years ago, in my first marriage, I was contemplating having children. There are several reasons I did not have them, but while I was trying to make up my mind I did what I usually do when perplexed — I public opinion polled.

There were many women in a small space on my job then and we all got along pretty well. Most were a little older than me and nearly all had children and had big family type photos on their desks and baby pictures. We all knew quite a bit about everyone’s kids. These were women in intact families with husbands making good salaries — and they made good salaries too. I’d call them middle middle class (they were not rich or classy — they worked in lower white collar jobs in school administration in Jax, Florida).

I must have talked with 4 or 5 of my women coworkers and just honestly told them I was trying to decide what to do and I was having trouble coming to a decision — what did they think? To a woman, they said virtually the same thing, which went like this:

“I love my kids, I’d kill anyone who touched a hair on their heads, but if I had it to do it over again I would have waited longer. I would have gotten more education, kept going at my career, traveled to see the world, experienced more of life first, read more books, written more poetry” — what ever the things were that they hating missing out on because raising children is such an all consuming project.

I was surprised because I was expecting them to tell me how great it was raising kids and that I’d better get going on it. My talks with them were influential in my decision not to have kids. I’d say these women had “birth regret” although I don’t think they’d have called it that.

* * *

Kathy:

I don’t think I’d call what you describe, Carol G, as birth regret, per se. To me, this outlines a feminist approach to becoming a mother — a message I understood in the 1970s. I did exactly what these women said they should have done before they had children, and I’m glad I did. Of course motherhood held me back in jobs anyway; no personal solutions to that big problem and I probably do have some health issues resulting from being an “older” mom. I agree with Ti-Grace who said, “I’m sure many love their particular children but the ‘mother’ role is a major bitch.”

* * *

Carol G:

Well, Kathy, they literally regretted having the children when they had them. And think about it — if they’d waited, anything could have happened. What’s interesting to me is why they went ahead before they really wanted to. I guess they didn’t know how terribly difficult it would be.

* * *

Ti-Grace:

Various women (feminists who have had one or more children) have told me over the years about a major annoying problem with urinary incontinence. This problem arose much earlier (in their 40s or even earlier) because of childbearing than it does in nulliparous women (for us, more like in their 70s). This was/is as a result of their internal organs being pushed out of place during pregnancy. The only adequate repair was through surgery. I have urged women to write about this but they’ve been embarrassed to do so. Too bad. This is a serious problem. And I don’t know if such surgeries are covered by insurance, etc. It might be considered “cosmetic” (but only by someone who has never suffered from urinary incontinence).

Is this what you had in mind, Kathy?

* * *

Kathy:

In terms of health, yeah, I’ve got the urinary incontinence thing, but I was mainly wondering if my thyroid would have gone out and whether I would have been able to regain my pre-motherhood weight if I had the children when in my 20s instead of mid 30s. Part of the weight thing is that tests of my thyroid didn’t depart from the so-called normal range for years (even though I had many of the signs of hypothyroidism right away) and part of it is that I never took time to take care of myself, I went right back to the lab 10 days after my first, and I worked at home feverishly slaving toward a grant deadline after my second was born.

* * *

Jane:

I am convinced that birth regret is widespread but we don’t call it that, or talk about it, because motherhood is put on a pedestal in the U.S. But we wouldn’t have so many foster homes if birth regret didn’t exist. And I suspect that what we call “postpartum depression” may actually be a form of birth regret.

I have found that older couples are more willing to talk about how sorry they are that they wasted so much time and money on raising kids. They feel there is no payback for their investment in time and money, mostly because Junior did not achieve what they hoped he (or she) would achieve—despite their sacrifices. I have heard stories from these parents of kids who were drug-addicted, alcoholics, obese, dependent or estranged, who became homeless or in trouble with the law—all to the despair of the parent who had sacrificed her life and income.

I have come to the conclusion that it is rare to have good, successful, undamaged kids in a society like ours. Hillary was right about one thing: It “takes a village” to raise a child. And we don’t have that kind of cooperation from our community.

Meanwhile, the life, hopes and dreams of the mother (and it’s usually the mother—the father doesn’t change his occupation because of parenthood) are gone, dissipated, wasted on years of routine childcare.

In some societies, like Nazi Germany, women were allegedly “forced” to bear children “for the fuehrer,” or so the folk tales go. In our society, there is certainly pressure on women to have children. In my day, it was rare for a married couple to choose NOT to have children. I think that’s partially due to religion. Catholicism, for example, condones the sex act only for purposes of reproduction.

Oddly enough — and I have thought about this often — very few of the feminist activists I knew in the ’60s and ’70s had children. Jacqui and I are just about the only ones I know of. And Alix has a child or two. All the others remained child-free all their lives and I often think that it was a good decision for them and for the movement.

I had to fight for my private time while raising my three kids. People disapproved of my divorcing my husband, leaving the suburbs, and moving to the City to pursue my career. I heard about it all the time. I was often told that it was a “selfish” thing to do. Yet, if we had moved for my husband’s career, it would not have been “selfish.”

Birth regret often continues long into the child’s adulthood. If you think kids become emancipated at 18 and then you are free to pursue your own life, you are wrong. I know one mother who had to call Social Services to remove her adult son from her apartment. She is a widow and living alone in as small Bronx apartment and she wanted her last years to herself but her son kept mooching off her.

My oldest childhood friend, a nurse, sacrificed her retirement money to send her two sons to college so they wouldn’t be saddled with college loans. Eventually, one became an auto mechanic, one became a bartender, She herself was a brilliant scholar and deserved to get an M.D. or Ph.D. in, say, hospital management, but she put her own ambitions aside for her sons. What a waste.

And then of course, the saddest of all: the woman who gives birth to a damaged child. If your child is born retarded or with cerebral palsy, your life as you know it is virtually over. There is no standard help for these parents and the rest of their lives will be eaten up caring for this child. It is a tragedy because there is no win-win in this situation.

Part of this rampant birth regret is due to the kind of society we live in, in America. The outside world does not care about your child. The competitive atmosphere pits kid against kid in school and in other activities. I’m amazed that any of them turn out OK.

I had a particularly hard time, as a single mother, because my ex-husband, miffed that I divorced him and moved to the big city, did everything he could to sabotage my child-rearing. His monetary contribution was minimal — $150/month per child — and he was a physician. The person who wants out of a marriage often takes a loss, and I was the one who wanted out. And remember that two of my children were unplanned. Yet I was the one saddled with their upbringing.

For example, during the 1970s, I needed to go to the hospital for a couple of days for minor surgery. I called my ex-husband (who had remarried and lived in a 4-bedroom suburban house), and asked him if he would take the children for a couple of days. He said no. “I’m not your baby sitter.” Those were his exact words! In other words, the children were my responsibility, 24/7, and that was my punishment for leaving him.

All the myriad tasks that make up childcare — the laundry, the daily routine, the food preparation, the dressing, the haircuts — are of no interest to the male parent and I have never known a male parent who has agreed to do them for any length of time. Some “househusbands” have tried it but they end up turning it back to the little woman when they discover what drudgery it is.

So is there such a thing as birth regret? You betcha! And it is long-term and complicated and sometimes tragic.

I don’t know what the answer is. Maybe change the world? Work for a world that cares about all people, including women and children? Release the woman from being enslaved to the denizens of the future?

* * *

Kathy:

I realized very quickly that parenting is the hardest and most challenging job I had ever embarked upon, harder than any of the scientific studies I ever conducted (rats don’t talk back) but I don’t regret having my children. I guess how you feel about parenting once the children are grown up depends on your hopes and expectations. My hope was that my children would grow to be politically aware, contributing members of society and I am happy to say I succeeded in attaining that goal.

I too think is very important to have time to do the things you can do as a single person before you begin the process because it is unrelenting and does tie you down. I was lucky enough to be able to travel a bit and I got my PhD before I had my first child. No doubt that having children (and admitting so during interviews — dumb!) adversely affected my chance of landing a full-time academic job. But I have to say, as I went to those interviews, I got more and more turned off by the all-encompassing nature of the work of a professor in this day and age. Nearly every young female prof in my field who I spoke with was close to having a nervous breakdown, not so the men, and having children had a lot to do with it. Not only are the women doing more of the housework and parenting, but social expectations of women’s involvement in parenting leaves every working mother feeling constantly guilty.

* * *

Ti-Grace:

I think that one of the worst curses that was laid on women was the false belief that it is possible to live your life through someone else’s! It’s like a “substitute” life. How can that ever work out satisfactorily?

I believe in friendship. And sometimes there could be sacrifice in that, but sacrifice is not the defining feature of friendship as supposedly it is in motherhood.

* * *

Jane:

Darling Ti-Grace, this is a brilliant observation. We all need to think about this. It is probably the biggest contributing factor for birth regret in the later life of mothers. Mothers give their all — their intelligence, creativity, time and talent — in raising their kids. But they get no payback after the job is done. Instead, they get rejection from their kids, as well as disapproval, criticism, blame.

If these mothers had put all that intelligence, creativity, time and talent into a career, they would at least have had a 401K. In devoting their lives to motherhood, they are rewarded with heartbreak.

* * *

Kathy:

My mother held that false belief all throughout her teen years and into married life. She mentioned her disappointment to me after all of us were out of the house — that raising children wasn’t enough of a life. Even though she was a terrific mother and all six of us are very different people doing different interesting things. I can’t remember if she told me that before or after I had my own children. But it wouldn’t have mattered; I had already surmised as much and was determined to do both, somehow. Of course I wasn’t of age in that exciting, totally engrossing period when you all were launching the WLM, if I were involved in the movement then I might have decided against having children too. I was in college in the ’70s, didn’t have my kids until the ’90s.

This has been a very interesting conversation about birth regrets/no regrets and decisions that each of us made. I wanted to go back and comment on Jane’s experience of single parenting. I can imagine how difficult it was, don’t think I could have done it. After I had my first one I became very aware how fortunate I felt that I had a partner that shared at least some of the work. And just my ability to say, “I’ve had it, can you take them for a while?”

* * *

Barbara:

I never regretted having a child though I might have done so if I hadn’t waited until I was 40. By then I had been able to enjoy the benefits of being single, to travel, to be sure I was in a relationship that would work for me long-term with a man who would assume responsibility as a father, would share (and equally neglect!) the housework. Who shared my politics. Time to develop a fair amount of job security and realize I didn’t care at all about having a career.

The downside? A very long and painful labor. Going through the inevitable craziness of the terrible twos, or threes or fours — or maybe all of the above — I do remember becoming so angry at one point that I was throwing pillows against the walls. The worries of having a preteen, which I think used to start at the teenage years. And so on and on. But I would have so much regretted not having my daughter, who in a way turned into my best friend, who I could turn to after my husband’s death, and who turns to me about her problems. I once thought when I was younger that I didn’t want a child but it would have been a major loss if I didn’t have her.

* * *

Ti-Grace:

What a nice story, Barbara. I’ve heard so many which did not turn out nearly so well. A luck of the draw?

* * *

Barbara:

The relationship with the man who became my husband took a lot of work over the years—with help from Carol H. (!) and the initial introduction by Kathie who was friends with him in the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi. Up to that point I had assumed I could never have a long-term relationship with a man. And of course raising a child took a lot of patience. If I had been interested in a career, I couldn’t have done it. The work world was a lot easier to manage in the seventies/eighties. The rest? Maybe the luck of the draw. My daughter was stubborn but so were we. I do think everything is much harder today. The daughter of an old friend of mine who lives in the same upstate NY town where we lived very recently died of a drug overdose despite rarely using drugs, just because the high school is flooded with them. That would never have happened when we lived there.

* * *

Pat:

I also had my one and only child at 40 having found my husband four years before that. I used to say, “How does anyone do it younger?” I did a lot when I was single and am grateful for the chance to travel and feel quite free. I have no bladder issues, thankfully. I had c-section for complicated reasons and not much labor.

* * *

Jane:

Barbara wrote: “The work world was a lot easier to manage in the seventies/eighties.”

Not so, Barbara. I found out, through experience, that most employers would not hire a woman who had three kids at home. The interviewer would ask questions like “Who takes care of the kids?” and “If your babysitter gets sick, do you have to stay home?”

I soon learned NOT to admit to three children. I admitted to one child — in case someone called my home and a child answered. I chose to admit to a son because a girl’s voice could be explained away as the babysitter. Years later, I learned that not admitting to having them affected my two daughters very deeply. They felt rejected by me! They did not know the workings of the work-world, so they did not understand why I did that. They did not know that I needed to do that to get a job to support them. I don’t think any of my employers ever realized that I had three children, nary a one. It was my deeply held secret. What a pity.

Hey, it’s a jungle out there.

* * *

Jane:

Ti-Grace is right about motherhood being a bitch, but how did you know? To the best of my knowledge, you are child-free. Lucky lady.

Am I the only mother who thinks motherhood sucks? We are so brainwashed by Mother’s Day and all that sacrificing crap.

* * *

Ti-Grace:

How did I know? I had a mother (born in 1899), who struggled hard for her graduate education. She believed that since women got the vote that a woman could have a life of her own. Turned out that wasn’t so easy. You could get an education but no job that fit this. Then, as now, the propaganda was that “you can have it all” — meaning a career and a family (meaning a husband and children). Rarely works out. The husband almost invariably has the better job, and income. He calls the tune for the family.

My mother had seven children, five of whom lived to adulthood. She had no career and I watched a very disappointed woman. I had four sisters and I observed their lives (I was the youngest). All had children. The happiest sister had only one child and she lived a pretty unconventional life, married to an artist.

No, I never had children. But I watched and learned.

Something else we need to discuss.

Life is a crap shoot. I knew that. Bringing someone else into this world — and who knows how that can turn out — is an awesome responsibility. In my view, that is “selfish”.

I believe that many women have children because it justifies their own existence. Most of us have been reproached for not having children. Subtext: “what else are you here for?”

* * *

Jane:

Good points, Ti-Grace. You are my fount of wisdom.

And you are right about child-free women being reproached. It’s like, “Oh, you poor thing, you have no children.”

Yet: Though we all know about Napoleon, does anybody remember his kids? Or George Sand, who has gone down in history as one of the earliest French feminists: how many people know that she had two children, a boy and a girl, both of whom she disliked and from whom she was mostly estranged in their adult lives. FDR has gone down in American history, but who remembers his kids? None of them — and there were about five — accomplished anything.

Women are tricked into thinking that we should devote ourselves to raising children instead of living our own lives fully and productively to the full extent of our talents.

Men do not understand my attitude about the need for women to live life fully outside the house and in the real world. My ex-husband would often say, “Women are lucky that they can stay home and be supported.” As though we did nothing at home but eat chocolates in bed.

* * *

Carol G:

Reproached is not the word for it. The Italian side of my family considered it on the verge of criminal that I had “deprived” my father of “his right to grandchildren” — his right no less that I had deprived him of. I had one cousin announce this publicly at a big family gathering. I should have slapped him.

* * *

Anne:

My experience in this lifetime did not include children, even tho I wanted them. I understand now, that LIFE decides which experiences we will have. And I can see now they were the right choices for me.

* * *

Basha:

Either way is okay!

For those of you who did not have children, you missed a shitload of anxiety.

And the heartbreak of a child growing up, leaving you, becoming critical of how you dress (me — sloppy) and not calling to see if you are okay. Not voting for Trump but living a much more upper middle class life (caring very much about fashion and the perfectly toned body). But the love I had for my little girl still fills my heart with gushiness of love.

My daughter, finally, finally begins to appreciate how hard it was for me as a single parent. Her husband was away and she was alone with a sick baby. For a night. So that has been heart warming — after all these years — for her to thank me.

My friends love and adore their children. But DAMN — it is so hard and I am glad the child rearing is over. Not suffering the heartbreak of the ungrateful child — Shakespeare said “sharper than serpent’s bite”—was another thing you have been spared.

One more thing, seeing my little girl become an emergency room practitioner and working with pediatrics and trauma victims made the whole thing amazing.

* * *

Carol H.:

Coming in late on this thread, but my parents sacrificed lots for me too, and I think I was both a disappointment and a source of pride to them during their lifetimes. I was the first in my family to go to college and they had great hopes for me and what did I do? I left a plum job (for a just-graduated journalism student) as a UPI reporter and ran away to join the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement and struggled financially from then on. After Mississippi, it was SCEF and the WLM. I think my mother had great sympathy with the WLM, even though she often found it a bit shocking and the cause of turmoil. My father kept her on a pretty short leash. Her labor was needed on the farm (as well as that of us children) and she did that in addition to nurturing us. She was a loving mother and I benefited greatly from her labor. (My father’s too, of course.)

My father only “helped” with the housework when she was bedridden when I was eleven. A lot of the housework fell to me when she was doing farm work. Like my father, she only had a high school education and had no place to run. Her only work experience before her marriage was cleaning other people’s houses from a young age.

BUT she was miserable (or seemed to be) when she was unable to have more children after my younger brother was born. She once told me that she had wanted at least half a dozen kids, but for health reasons had to settle for three. I did not want my mother’s limited life and she did not want it for me. She insisted I go to college, no matter what, and saved from the egg money to buy me a little portable typewriter when I was in high school.

Then came the exciting “movement days” of the ’60s and ’70s when stopping to have a child seemed out of the question. I did always expect to have at least one, though — someday — especially after the WLM raised my expectation that things would surely change for women before my clock ran out. By the time I was ready to reconsider and began to discuss this with my mate, he left me (and partnered with a man and got AIDS). I was never able to find a man after that who I thought would make a decent father and long-term mate. I had always been sure that I did not want to raise a child on my own, so I didn’t have any. Having foregone any chance at a career by then, I was struggling just to support myself and knew I couldn’t also support a child. That would be a bigger sacrifice than I was willing or able to make.

I never looked on this aspect of my life as much of a “choice” (except for using birth control, of course). Although I’ve wished from time to time to have a family (especially now that I’m old and growing more dependent), I have little “no-birth regret” that I was able to spend the time I did in movement work. A phrase from a Malvina Reynold’s song often comes to mind: “a workingclass woman and a red…and all the world’s children were mine.” In one sense, not having a child was a personal sacrifice, but since becoming a feminist, I’ve understood it as having both a good side and a bad side. The bad could only be largely alleviated if “mother’s work” could ever become “parent’s work” with society as a whole picking up the slack.

I’m not sure what I think of the word “sacrifice” here. “It’s complicated,” as they say.

- * *

Peggy:

Surely I mentioned in a consciousness-raising session at the SCEF office [editor’s note: back around 1968], but maybe the strongly prevailing respect for her silenced me: I read Simone Beauvoir while in a home-for-unwed-mothers, and never trusted her as our intellectual mother because she did not experience the realities of most women, who have to raise children.

Maybe I was preoccupied with no one ever saying “me too” when I made myself share my hardest experience as a woman: giving up a child for adoption. I know I did share that, because it was traumatic ‘tho purgative too, and lonely, every time.

By the way, if this IS about regret, rue, ruing that you don’t have children, forget it. Get over it. They, at least mine, both boys, do not prove “that my livin’ has not been in vain.” They do however know “the clitoris, and only the clitoris, is the seat of the female orgasm” thanks to Anne Koedt—and their father—and my nagging him to be sure.

* * *

Carol G:

I think I have had the reverse of birth regret — don’t know what to call it. Happiness that I didn’t have children? Off and on after menopause I’d wonder if, and sort of fear, that the day would come when I’d find myself regretful, unfulfilled, lonely — it hasn’t happened though. Often funny kids in the subway singing a rhyme make me smile. I exchange silly faces with a baby at the same time grateful as can be for being unencumbered with lifelong responsibility for them.

My beloved father — a doll — wanted a PhD in the family so much. He was in his 80s splitting his social security check with me so I could finish grad school without debt. He felt responsible for my happiness and financial independence no matter how bad I was, how many things I did that upset him, or how old I got. I don’t think I could be or want to be in that position. I know my mother especially, but father too, “sacrificed” for me — e.g. they lived in my grandmother’s house because the neighborhood and schools were better for me than what they could afford on their own. They were very unhappy in that house. My grandma was Boss there in every way.

I don’t think you can help “sacrificing” if you have kids. I know my mother would have rather kept writing than come when I needed her — how could she not have? — one has to go when kids need you. She was never bitter or unpleasant to me about it. I think where it came out was in disappointment with the product — me — that she gave up so much to take care of me.

I think our wretched system racism/imperialism/male supremacy sets up this contradiction between children and parents and both pay for it their whole lives.

If we had all the things we need — a short work week, guaranteed annual income, free 24 hour childcare and shared between both parents and community, national health care, paid parental leave, free community based care for seniors, workers comp for pregnancy complications (like the urinary thing you were talking about, Ti-Grace), social security paid in if parents stay home raising kids, pre-K, free summer camps and on and on — then parents and especially moms would be able to be artists and pilots and statespersons and so on.

Regarding Beauvoir, I feel I should mention that one of her first actions with the Mouvement de Libération des Femmes was in defence of teenage mothers, at a home for pregnant teenagers: it was run by nuns, one of the immediate concerns was that their treatment of the young women was extremely strict bordering on abusive. Another concern was the assumption that, because they were pregnant, their prospects in life and in their education had to be so severely limited, mostly to the strict minimum plus some vocational training: the assumption was that, because they’d got pregnant, their lives were completely ruined.

I’ve noticed that she elicits quite strong feelings, and it’s not the first time I’ve heard that her childlessness makes her a poor feminist, or that she shouldn’t talk about motherhood because she hasn’t directly experienced it. I haven’t actually found much feminist writing on motherhood as yet, Beauvoir’s being based mainly on sociological and psychological case studies, as she had no direct experience of motherhood.

As for my own relationship to having children, I mostly feel indifferent to the idea, I think it might have been cool, but I have no regrets about not being a mother. I’m bordering on too old to consider it now. If I felt strongly for or against having kids, then it would definitely require thought. The aspect of it that does elicit strong emotions for me (anger and frustration, to be precise), is that there’s a tendency to treat childless women as if they’re incomplete, they’re still children themselves somehow.

On the one hand, it’s an experience I’ll never have, obviously an intense and life-changing one. It’s a huge deal, physically and psychologically. On the other hand, I rarely see men, as such, reduced to their lived experiences the way women are (this does happen to them if they’re being identified in some way as working-class or of colour or gay, etc.). And it’s a daily thing, coming mostly from other women, in small and in big ways. It’s amazing the casualness with which, sometimes, other women will outright tell you you’re incomplete until you’ve had a child, or say of a woman who just got married or had a child “she’s a woman now”, as if she was a kind of half-formed sexless potato-entity beforehand. It can also cast a shadow over someone’s years of work, not to be the incarnation of what they presume to write about. This isn’t even particularly a point about motherhood, but regarding Beauvoir, for instance, I see it all the time that her personal experience is more important (positively or negatively) than her scholarship, writing or activism. I never see anyone read Sartre and say “but he didn’t actually chop any wood in the forest”, usually it’s his reading of Heidegger that’s critiqued.

That said, womanhood is a huge deal physically anyway. We undergo massive physical transformations, based on the potential of housing a whole new life for nine months, whether that happens or not, whether we’re even able to bear children or not. A lot of us would probably be put out if our uterus started just sending us a text message each month (“congrats, you’re not pregnant and everything is working fine”) instead of going through the whole menstrual experience. It’s kind of terrifying that this translates to our main line of defence being to own our bodies, to have a relationship of property with them: to have the title deeds of the property restored to us. I don’t believe men have to do this, they just walk around like, “I’m George”, because there’s no presumption that they’re each man’s private property in the first place. Whereas each woman has had an experience where a random stranger in the street acts towards her like the welcome chocolate on his hotel pillow somehow grew legs and walked away from him. And it shows that women are the first objects of exchange. At the same time, there are real human relationships behind this: it should be possible to reject the ideology without throwing out the relationships themselves.

The following comment is from Carol Downer (posted by the Editors):

This discussion bothers me for two reasons.

First of all, the Abortion Regret claim has been well researched and confirms what those of us who work at abortion clinics have found, very few women regret having had an abortion. So refuting it with a “birth regret” column is buying into the anti-abortion movement’s myth.

Second, the discussion reminds me of my pre-Second Wave days when we certainly did talk about how hard it is to be a mother and how heavy the burden is and what a rotten world we have to raise our children into. One need not be a feminist to understand that. In the Second Wave, we raised our consciousness to see that this an artificial dilemma that women face due to living under patriarchy. I didn’t see that awareness coming out of this discussion. In fact, I saw writers who don’t have children being either defensive about not having children or “offensive” in labeling motherhood a “bitch”.

The question isn’t whether to become a mother or not, the question is the changes that must be made so that society as a whole provides women with reproductive choice. Our biology determines our destiny only to the extent that the male sex rules over the female.

Thanks for this comment Carol Downer– we all knew that the idea of abortion regret was a myth, I’m glad you made that explicit. We played off that language but I don’t think we bought into it. Actually, I think a big question is indeed whether to become a mother or not. In the past women weren’t able to make that choice, now we can and should. And I heartily agree that we need to remake society such that the rearing of children doesn’t fall so heavily on women’s shoulders

Actually, I think it’s getting harder again to make the decision to have a child or not, for two reasons:

– abortion rights are under attack in many places

– but also, many women decide not to have children because they just can’t afford to. I know this was a major consideration for me, and if I did feel strongly about wanting children, I don’t think it would have been feasible anyway. There’s still major pressure on women in both directions, often at the same time.

The other aspect that comes into discussions of this topic is that regret is a major part of life anyway, we all have regrets, or we wouldn’t be human, and this is one regret – either way – that women just aren’t trusted to be able to handle a lot of the time. Does the sentence “you’ll regret it” have to carry so much weight in this particular case? I think it’s what infuriates me the most, not the notion that I should or shouldn’t have a child, but the idea that the regret is some mystical burden For Women.