By Carol Hanisch

They call us Nazis and say that we are no better than Hitler because we think a woman should have be able to choose whether she gives birth to a seriously sick child – but we are used to such comparisons. They say these things about us because they are frightened. The government of Poland did not expect such huge protests against its proposed ban on abortion. In the last week, 7 million women were on strike all over Poland to protest against the draconian law and pushed the government to back down.

– Krystyna Kacputa, “This victory on abortion has empowered Polish women – we’ll never be the same”, The Guardian, Oct. 6, 2016

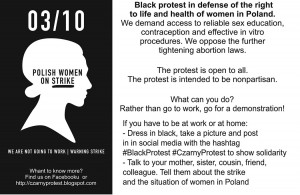

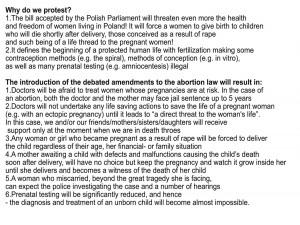

These are the words of one of the organizers of the massive national strike by Polish women against a proposed law to make abortion in their country entirely illegal and punishable of both the woman seeking an abortion and any doctor who performed them. No exceptions, not even in the case of rape or health of the woman or fetus.

The women won. The proposed law has been withdrawn – for now. It could be resubmitted.

Being called “no better than Hitler” was not the only invective hurled against the women, but the disrespect only made them angrier. “I have worked in reproductive rights in Poland for 25 years,” Kacputa wrote, “and we used to be happy if 200 women attended our protests.” But that changed with the strike:

(Protest Flyer above. Click to enlarge)At first politicians ignored us, then they enraged us with their words. The foreign minister, Witold Waszczykowski, said: “Let them have fun. They should go ahead if they think there are no bigger problems in Poland … We expect serious debate on questions of life, death and birth. We do not expect happenings, dressing in costumes and creating artificial problems.”

These words mobilised even more women. I have never seen such huge protests. Something snapped in Polish women; we are empowered and we won’t stop. The protests were so spontaneous: with barely a few days’ notice thousands of women were walking out of work, and if they couldn’t get the day off, many told me, they said to their bosses they would not return because they could not work alongside people who did not believe in their rights.

The BBC reported that the strike in Poland was inspired by a 1975 national strike in Iceland.

In Iceland

Gatherings in support of the Polish women’s strike were held in several countries. In reporting a solidarity protest by hundreds of Icelandic women, the Iceland Review pointed out that on October 24, 1975, ninety percent of Icelandic women had gone on strike with much broader demands, refusing to work, cook or look after children (above photo). Thirty years later, Annadis Rudolfsdottir recalled the protest:

When the United Nations proclaimed 1975 a Women’s Year, a committee with representatives from five of the biggest women organisations in Iceland was set up to organise commemorative events. A radical women’s movement called the Red Stockings first raised the question: “Why don’t we just all go on strike?” This, they argued, would be a powerful way of reminding society of the role women play in its running, their low pay, and the low value placed on their work inside and outside the home. The idea was bandied about, and finally agreed to by the committee, but only after the word “strike” had been replaced with “a day off”. They figured this would make the idea more palatable to the masses and to employers who could fire women going on strike but would have problems denying them “a day off”. …

Gerdur Steinthorsdottir, then a 31-year-old student at the University of Iceland and now a teacher, helped organise the rally. She claims the participation was so widespread because women from all the political parties and the unions felt able to work together, and make it happen. …

Iceland’s men were barely coping. Most employers did not make a fuss of the women disappearing but rather tried to prepare for the influx of overexcited youngsters who would have to accompany their fathers to work. Some went out to buy sweets and gathered pencils and papers in a bid to keep the children occupied. Sausages, the favourite ready meal of the time, sold out in supermarkets and many husbands ended up bribing older children to look after their younger siblings. Schools, shops, nurseries, fish factories and other institutions had to shut down or run at half-capacity.

The women responsible for setting Morgunbladid, one of Iceland’s main newspapers, returned Cinderella-like to work at midnight. The paper was half its normal size the next day and contained only articles about the strike. The bank tellers who saw their positions filled by male superiors took special pleasure in going to the bank and keeping them busy. It was a moment of truth for many fathers who were exhausted at the end of the day. Not surprisingly this day was later referred to by them as “the long Friday”.

Icelandic women held similar protests in 1985, 2005 and 2010. The 2010 action took on a more militant title: “Women Strike Back.” Today Iceland is considered one of the most “women friendly” countries in the world.

In Spain/Catalonia

We reported here the 2014 Vaga de Totes strike which proclaimed “Women move the world. Stop now! All on strike!” Women took over the streets in Barcelona demanding an end to the “social, economic and legal policies that severely undermine our rights, dignity and freedom.”

In the USA

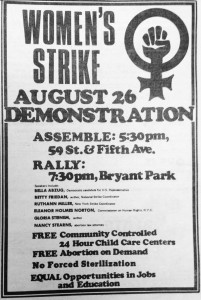

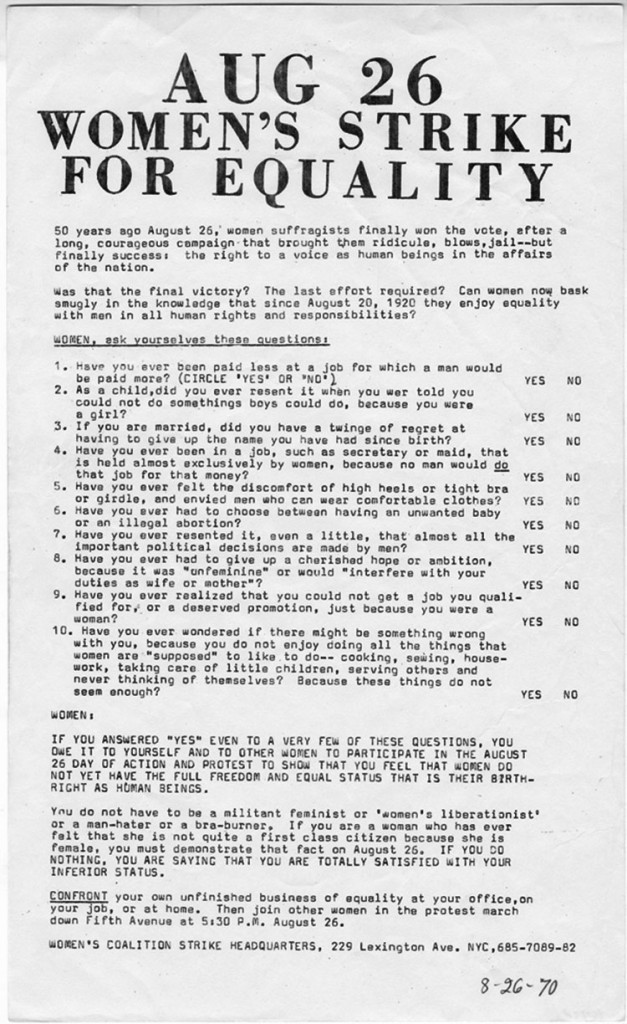

In 1970, the U.S. had a national “Women’s Strike for Equality” on August 26, the 50th anniversary of women winning the vote. Betty Friedan had proposed the Strike at the end of her outgoing speech as President of the National Organization for Women (NOW) in March of that year. In It Changed My Life, Friedan wrote:

Above: Ad in the Village Voice Below: Broadside for the StrikeThe media was still treating the women’s movement as a joke. And fear of ridicule still kept a lot of women from identifying themselves as feminist…. We needed an action to show them – and ourselves how powerful we were. … we needed an action women could take in their own communities without much central organization. A woman from Florida, Betty Armistead, had written me about a general strike of women that had been proposed in the final stages of the battle for the vote, reminding me that the fiftieth anniversary of the vote was August 26, 1970.

On the plane to Chicago, I decided to propose such a strike on August 26, 1970, on the unfinished business of women’s equality. I told [the women from Chicago NOW] who met my plane and they were immediately fired by the idea. … We were a small organization, then, to mount such a huge action – but I sensed that the women “out there” were ready to move in far greater numbers than even we realized. To call on women anywhere to get together, and strike, symbolically, would…kindle a chain of reaction among women that would be too powerful to stop or divert or manipulate – or laugh at or ignore. …

The NOW members had gasped and cheered at the idea of the strike. But the next morning [some NOW members] opposed wasting NOW’s resources on such a wild scheme…. I said it wouldn’t, shouldn’t be solely a NOW venture; it would only work if launched by a larger coalition. But the NOW convention had voted to support it.

Although the New York march received most of the attention, there were events in some 92 cities and 42 states. In New York City, some 20,000 to 50,000 thousand women (depending on the source you choose) marched down Fifth Avenue. It culminated a week of events there planned by an ad hoc coalition of more than 50 women’s groups from across the feminist spectrum. A group of women had hung a “Women of the World, Unite!” banner from the of the Statue of Liberty to publicize the Strike. Militant home-made picket signs abounded, such as:

Don’t Iron While the Strike Is Hot Don’t Cook Dinner — Starve a Rat Today Housewives Are Unpaid Slave Labor.The Strike was front pages news. Time magazine warned in the opening paragraph of its coverage:

These are the times that try men’s souls, and they are likely to get much worse before they get better. It was not so long ago that the battle of the sexes was fought in gentle, rolling Thurber country. Now the din is in earnest, echoing from the streets where pickets gather, the bars where women once were barred, and even connubial beds, where ideology can intrude at the unconscious drop of a male chauvinist epithet.

The day and the Movement it represented, however, did not prove to be “too powerful to…divert or manipulate.” See “Misnamed ‘Women’s Equality Day’ Obscures the Past and Present Struggle” on the Redstockings* blog “What Is to Be Done.”

Though such national strikes and other large mobilizations are certainly ot the only tactic to be used for women’s liberation, when women go on strike, they often feel their power not just as an individual but as a class–the authentic meaning of the 1960s slogan “sisterhood is powerful.” The “I” becomes a “we.” Another generation is learning this. One of the Polish protesters, Aleksandra Włodarczyk, 28, put it this way:

“In previous anti-government protests, it was our parents’ generation on the streets, but with this, they have managed to mobilise the young, and we are very angry.”

***

* Redstockings was the name taken by a U.S. women’s liberation group formed in 1969 as described in the book Feminist Revolution “The name Redstockings was intended to represent a synthesis of two traditions: that of the earlier feminist theoreticians and writers who were insultingly called ‘Bluestockings’ in the 19th century and the militant political tradition of radicals– the red of revolution.” Redstockings’ theoretical work was known internationally and several groups in both our own country and in other countries, took the name as well. It was great fun to see in the article quoted above that the radical movement of feminists in Iceland is called the Red Stockings movement! -Eds.

# # #